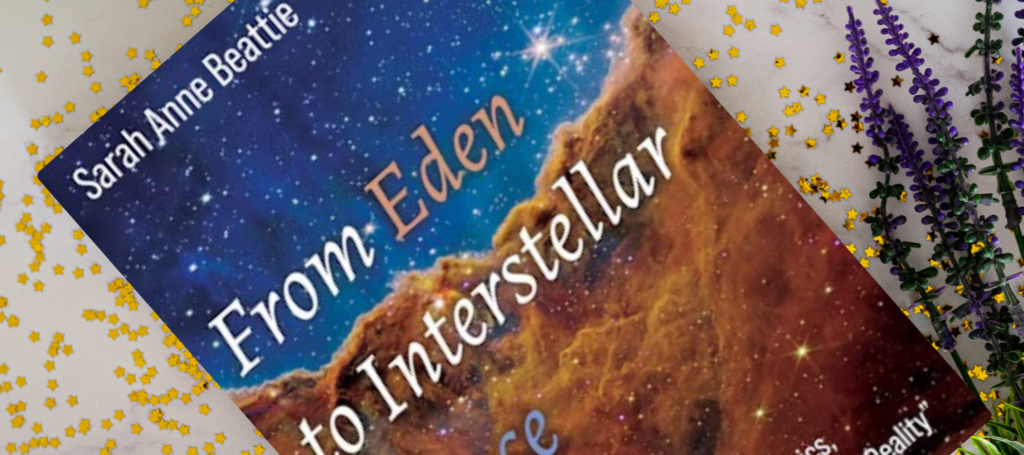

This reflection celebrates Sarah Anne Beattie’s marvellous achievement in From

Eden to Interstellar Space. I would like to call this little response to Sarah Beattie’s

work, “Going Beyond the Bitter River.” In this I draw from the beautiful way Sarah’s

book begins with a utterly disarming juxtaposition between the world’s oldest map,

Babylonian, (drafted well before the Bible), in which a “Bitter River” encircles the 6th

century earth, and a CMB map more recently drafted on a satellite in space that

captures the afterglow of the Big Bang. These are metaphorical bookends of a work

that is not only ambitious but profoundly moving, so, a glimpse into From Eden to

Interstellar Space.

What is its question, this work? At its heart, this book dares to ask: Can faith and

science not just coexist, but actually expand each other’s horizons? Sarah draws

inspiration from an unlikely source, philosopher and atheist/non-theist Thomas

Nagel, who questioned whether the materialist scientific worldview is really enough

to explain consciousness, meaning, and reality.

Sarah’s project takes up this challenge with remarkable skill and dauntless curiosity.

With Nagel as perhaps reluctant comrade, she traverses the fields of theology,

biblical studies, philosophy, ancient literatures and mythology, and then equally

ambitious fields in science — astronomy, cosmology, quantum mechanics — without

losing hold of her golden thread. Where many might struggle in such vast

interdisciplinary twists and turns, Sarah finds her way into the very centre of the

labyrinth — and there she finds something incredible (a Minotaur? Or something

else?).

In From Eden to Interstellar Space the method is complex. Sarah weaves ideas from

disparate disciplines together like Ariadne: careful, intricate, but also bold and

imaginative. The result is a surpising hermeneutic — a way of reading biblical texts

that is expansive, original, and honouring—deeply respectful of both ancient

traditions and modern scientific insight, and held steady by Nagel’s will to

authenticity.

Sarah’s work isn’t about defending religion against science, or science against

religion. It’s about rethinking both that seem to lie at opposing ends of an

epistemological spectrum. With a set of test cases, she argues that biblical

narratives — like the story of Eden, the Annunciation, and the cosmic battle in

Revelation — are not outdated myths. They are, instead, examples of humanity’s

courageous attempts to map realities that are, even now, beyond comprehension.

Thus Sarah stages a stunning and compassionate conversation between the ancient

imagination and space-age consciousness — and shows that rather than competing,

these two can together extend the boundaries of the thinkable.

My respect for Sarah’s work is unreserved. I commend her not just for a truly

exemplary intellectual expertise, but for the bravery and generosity of her thought. I

am not overstating it to say, From Eden to Interstellar Space: Thomas Nagel, Biblical

Hermeneutics, and the Search for “the True Extent of Reality” is indeed a

masterpiece — intellectually rigorous, creative, and very much needed in a troubled

world. If I could compare this work to anything, it is Terrence Malick’s (2011) film Tree

of Life — it evokes in me a similar sense of cosmic wonder, this unfolding and

refolding of time and space, superb intricacy, robustly anchored in philosophy and

theological/biblical knowledge. Within the pages lies a rich integrity in terms of care

of the sacred, not too faint-hearted to explore creative or novel routes in theology

and thus beautifully capacious in its open-ended notions of spirituality. It seems like

the horizon of creation is caught in one’s gaze. From Eden to Interstellar Space is

not just a book about belief or science. It’s a breathtaking invitation to think, and to

believe, more expansively and more authentically.

In this era where knowledge is routinely distorted by hollow men, Sarah’s work

reminds me that the quest for truth — whether scientific, philosophical, or theological

— requires courage and always comes at a cost. I want to return to the Bitter River

here. Stepping into it (stepping into a PhD or writing a book) means stepping into

the unknown where monsters, wonders and strange beasts lurk. It requires at times

a hero’s quest beyond what has previously been thought, and at the outset begins a

journey beyond the comforts of hearth and home. Bilbo Baggins would say, “It’s a

dangerous business, Sarah, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you

don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.” As Sarah

writes in her epilogue going out her front door led her to wondrous and sometimes to

very lonely places. It is a secret cost that fewer and fewer in our old circles truly

understand this kind of intellectual and spiritual pilgrimage.

Sarah, in your embrace of theological complexity, your openness, and willingness to

let imagination and reason work together rather than tearing them apart, you became

in this book a little like a biblical prophet of old, wandering the magnificent expanse

of wild places—star fields above, mountains afar off. You beheld holy fires on the

limbs of desert trees, and, on the zephyrs of evening you heard the lilting echo of the

still, small voice of your god.

Thank you for writing this book.