“We are rooted in where we have come from but we are unfolding something new. This is a powerful idea of what needs to be happening within schools. There will be, I think, problems for many schools as they try to engage with Te Ao Māori. The challenge of mātauranga Māori is to integrate a very spiritual outlook on the world and on life, with a very non-spiritual framework.”

“The koru, which is often used in Māori art as a symbol of creation, is based on the shape of an unfurling fern frond. Its circular shape conveys the idea of perpetual movement, and its inward coil suggests a return to the point of origin.”

Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, ‘Māori creation traditions – Common threads in creation stories’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, (accessed 28 March 2022)

Photo: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/photograph/2422/the-koru

I was born in the late 50s, and I grew up in a New Zealand (not an Aotearoa!) that was tied to Britain. I grew up in a very white world. As I entered a Christian school as a teacher I wished to integrate my faith into my teaching, I realised that my outlook was very materialistic. I don’t mean that I was always going shopping for many things, but the world I lived in was a material world. Spiritual matters were a separate thing. Even in a Christian school the integration is not strong. I still find myself coming up against the materialism that underpins Western assumptions; success is measured in credits, grades, going to university, getting a good job.

As I studied physics I grappled with this duality; my faith on one side and physics on the other. They did not integrate. I rarely confessed to my fellow students that I was Christian. For many, you couldn’t be an intellectual thinking person and also hold a faith position. So I stayed quiet. In state schools one is not allowed to bring a faith perspective into one’s teaching. I can teach you about physics and I don’t have to mention God once. I have now moved across into a Christians school and I am now expected to bring faith in. I no longer see that division. But I think this will be the issue for our schools in bringing in mātauranga Māori. It presents something of an existential threat to the way schools think about things. It will even challenge the power structures that schools operate in.

“Ehara i te aurukōwhao, he takerehāia”

Not a leak in the upper lashings, but an open rent in the hull! (Elder, 2020)

This whakataukī struck me because it was happening for me – not just a leak in the sails but a major tear in the hull. My whole world view had to shift. What I was learning was shaking my world.

Here is what I was reading:

- McGrath: “The re-enchantment of nature”; “Inventing the Universe”

- Meek: “Loving to know”; “A little manual for knowing”

- Moltmann “God in Creation”; “The trinity and the kingdom of God”

- Newbigin: “Proper confidence”

- John Polkinghorne: “Science and the Trinity”

- Ruka: “Huia come home”

- Linda Tuhiwai Smith “Decolonizing Methodologies”

- James K. A. Smith: “All things hold together in Christ”; “Who’s afraid of postmodernism?”; Cultural liturgies Vol 1-3

- Rev. Māori Marsden “The Woven Universe” (compiled by Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal)

- N. T. Wright on Lesslie Newbigin: “if all truth was God’s truth, then there was no area of life over which human research could claim absolute rights…there was no such thing as neutrality or “objectivity… All the truth we see in whatever sphere comes with strings attached” (Wright in Goheen (2018), p. x)

Mātauranga Māori is a spiritual way of looking at things as much as it is about the physical world. This naturally connects with scripture. John 1:2: “Through Him all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made.” The world was not just made but it was made through Christ, so there is a deep intrinsic sense of things being held together.

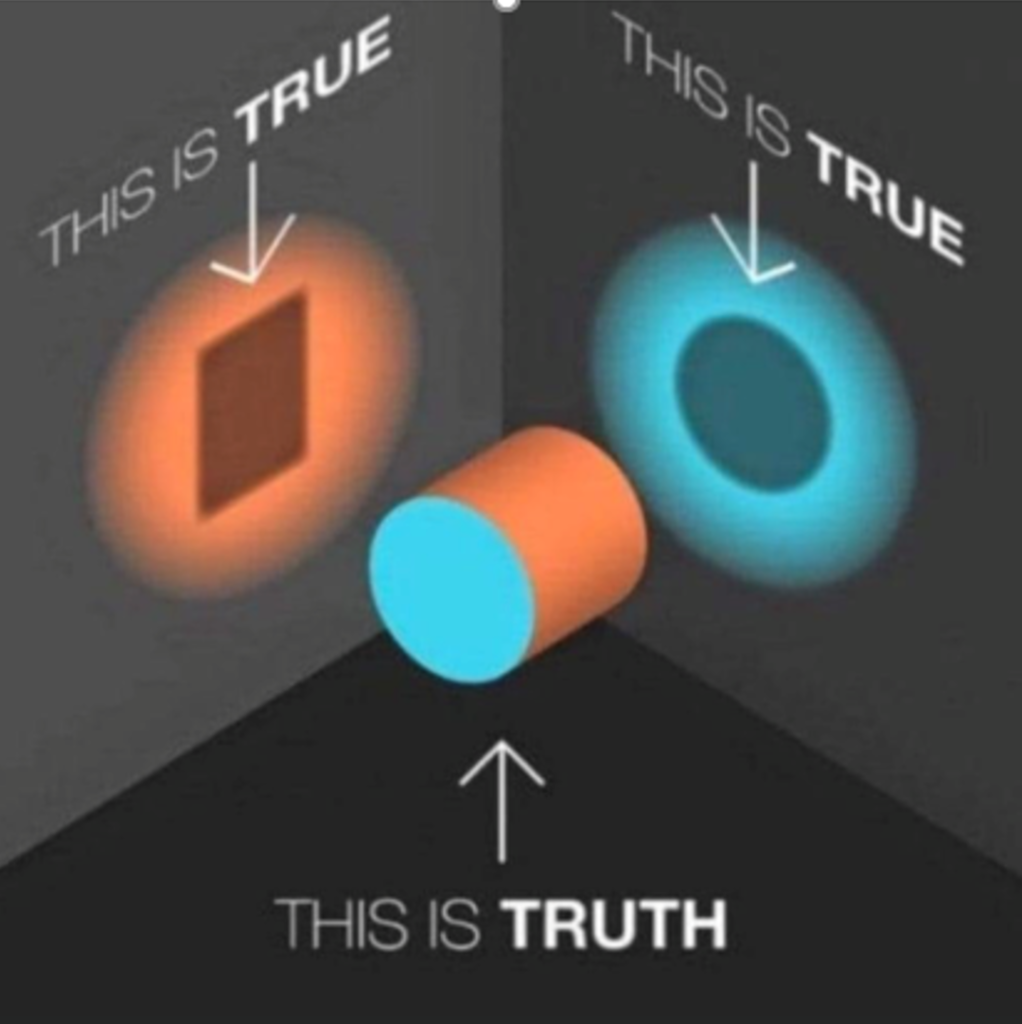

Engaging with mātauranga Māori is a bit like the wave particle duality in physics. What is light? I can show you that light is a particle. I also have equipment at my school that will show you that light is a wave. Which is it? The answer is – both! It is a mystery. It is hard. Modern physics has been driving people bananas for years! We know it works but we don’t really know how.

The image of the pipe fitting through both a round hole and a square hole is a way of visually explaining how you can look at things from different perspectives and see different things.

God is God, not either ‘this’ or ‘that’, so what other universe could a Trinitarian God have created? Colossians 1:17 suggests that God is present here in this room, containing everything and ensuring that everything continues to exist.

My role as a Christian science teacher is to challenge my students to see beyond what is in front of them; to see not just with their physical eyes but with their spiritual eyes as well.

Nichols: “Knowing is more than just looking and sensing; reality is greater than what is known by the senses; we can know what we cannot see” (2003, p.225).

This is vital in recovering a sense of the relationality of all creation. Māori have not lost this. Māori, as I understand this, relate to the natural world in an ‘I-Thou’ relationship, as McGrath, quoting Martin Buber, puts it. This makes perfect sense from a Trinitarian theology. But I find that most Pākehā Christians are closet deists in a dualistic framework.

We are not being asked to jettison what we know, nor how we know, but to “enlarge our tent” (Is 54), to ‘unfurl’ but retain our roots. We have to start removing the chains that the Enlightenment put on to Western science. We need to appreciate there are different ways of knowing, of gaining knowledge and applying it. As Augustine said, “To believe is to see” (Fides quaerens intellectum).

Mātauranga Māori has striking parallels with emerging contemporary understandings of creation as interconnected and relational. This has been lost to a large degree in our teaching of science. I see the new standards as seeking to recover this. Linda Tuhiwai Smith points out that “Indigenous knowledge in terms of the environment is well recognised. However … it extends beyond the environment; it has values and principles about human behaviour and ethics, about relationships, about wellness and leading a good life. Knowledge has beauty and can make the world beautiful if used in a good way.” (Smith, 2021, p31)

Moltmann (God in Creation) “if we want to understand what is real as real…we have to know it in its own primal and individual community, in its relationships, interconnections and surroundings. We no longer desire to know in order to dominate, analyse and reduce in order to reconstruct [but] to participate, and to enter into the mutual relationships of the living thing.”

Christian theology, in particular Trinitarian theology, offers a way to integrate Mātauranga Māori and western knowledge systems and validates the overt presence of a special character in the science curriculum.

One vital component of Christian theology is Christ’s self-kenosis (Philippians 2). God’s kenotic self-giving action in creation is a model for our interaction with Mātauranga Māori in Science teaching. Polkinghorne “…the act of creation is an act of divine kenosis” (p. 96). In other words, we engage very humbly. We do not approach this thinking “I know what I am talking about.” Humility takes us out of our Western assumptions and allows for the possibility of what we do not know.

Implications for science teaching in Christian Schools

How does this work itself out in a school science department?

In the old NCEA standards, science had no reference to mātauranga Māori. The new Learning Matrix is part of our whole national move towards recognising Māori as the tangata whenua. New stardards are being used as assessment instruments. Some of these new stardards specifically reference Te Ao Māori, for example:

- “Te ao Māori acknowledges the interconnectedness and interrelationship of all living and non-living things. Understand the cultural significance for Māori of seeking to understand the total system …”

- “understand that the taiao is centered on mauri, and encompassed and maintained by kaitiakitanga, and described in science as consisting of interacting spheres …”

- “Explore how mauri is an essential part of the natural and human-constructed world and how it is essential to maintain or restore mauri.”

How is a secular state school going to teach ‘mauri’? I think this is going to be challenging because it is a spiritual concept. In a Christian school we can engage with it through our conviction that the world is held together by God. God’s very presence infuses through the universe.

It is also challenging for Christian schools to not assume that ‘mauri’ is the same as the Holy Spirit as we understand it. It is too easy for us Pākehā to incorporate insights from others and carry them off!

What I am saying is that a Christian faith framework enables points of connection with mātauranga Māori. For me, this begins from honouring God as both Creator and “a creative presence within” the world (McGrath, 2002, p. 49). I would affirm with Polkinghorne that “…the general character of physical reality seems to correspond to a web-like character of interconnected integrity.” (Science and the Trinity, 2004, p. 74). This theology enables openness to Te Ao Māori, and helps us become more holistic in how we engage.

In summary:

- A Trinitarian Creator implies an ‘enchanted’ universe

- This is not new, expressed in Celtic and Franciscan Christian theology (McGrath, 2002, p. 186)

- Modern discoveries in physics (and other sciences) point to a relational universe (Marsden, 2003; Polkinghorne, 2004)

- Mauri is not an untenable concept in a Christian school

- Christian anthropology as per Genesis leads to a whakapapa with the natural world

- Awe and kenotic humility are the keys to the true science endeavour

So how do we implement this in an authentic, Christian manner?

Some suggestions for a Christian school:

- To approach this change with kenotic humility and respect (Polkinghorne; Augustine)

- to design Science units that cross the boundaries of physics, chemistry & biology & theology, re-sacramentalizing the created world (Boersma), telling stories of redemption, not merely “facts”

- to emphasise communal learning and communal assessment – Whanau and Whakapapa

- to contextualise teaching in the local environment.

- To be led by and in partnership with the relevant Māori community – Tangata Whenua/local Kaumātua.

References

Blomberg, D. (2007). Wisdom and curriculum: Christian schooling after postmodernity. Dordt College Press.

Boersma, H. (2011). Heavenly participation: The weaving of a sacramental Tapestry

Bonnet, C. M. (2020). Christian leaders as storytellers: C. S. Lewis, God’s master storyteller. In J. D. Henson (Ed.), Modern metaphors in Christian leadership: Exploring Christian leadership in a contemporary organizational context. Palgrave Macmillan.

Brueggemann, W. (1982). The creative word: Canon as a model for Biblical education. Fortress Press.

Golliher, J. (2021). The Franciscans form of service: Hopeful reflections in a perilous time. Third Order, Society of St Francis. https://tssf.org.uk/about-the-third-order/further-resources/The-Franciscan-Forms-of-Service

Lewis, G. & Barnes, L. (2016). A fortunate universe: Life in a finely tuned cosmos. Cambridge University Press.

McGrath, A. (2002). The re-enchantment of nature: Science, religion and the human sense of wonder. Hodder & Stoughton.

McGrath, A. (2015). Inventing the universe: Why we can’t stop talking about science, faith and God. Hodder & Stoughton.

Messmore, R. (2018). The trinity, love and higher education: Recovering communities of enchanted learning. In J. M. Luetz, T. Dowden, & B. Norsworthy (Eds.), Reimaging Christian education: Cultivating formative approaches. (pp. 39-50). Springer.

Moltmann, J. (1981). The trinity and the kingdom of God: The doctrine of God. SCM Press.

Moltmann, J. (1985). God in creation: A new theology of creation and the Spirit of God (1st U.S. ed). Harper & Row.

Newbigin, L. (1995). Proper confidence: Faith, doubt, and certainty in Christian discipleship. Eerdmans.

Nichols, T. L. (2003). Sacred cosmos: Christian faith and the challenge of naturalism. Brazos Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (2004). Science and the trinity: The Christian encounter with reality. SPCK.

Reid, J., Rout, M., Tau, T. M., & Smith, C. W.-R. (2017). The colonising environment: An aetiology of the trauma of settler colonisation and land alienation on Ngāi Tahu whānau. UC Ngāi Tahu Research Centre.

Smith, J. K. A. (2010). Thinking in tongues: Pentecostal contributions to Christian philosophy. Eerdmans.

Smith, J. K. A. (2013). Imagining the kingdom: How worship works. Baker Academic.

Smith, J. K. A. (2018). Introduction. In Smith, J. K. A. & Gulker, M. L. (Eds.) All things hold together in Christ: a conversation on faith, science and virtue. (p. xx). Baker Academic.

Smith, L. T., (2021). Decolonising Methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Van Dyk, J. (2007). Foreword. In Blomberg, D., Wisdom and curriculum: Christian schooling after postmodernity (p. ii). Dordt College Press.

Wright, N. T. (2018). Foreword. In M. W. Goheen, The church and its vocation: Lesslie Newbigin’s missionary ecclesiology (pp. ix – xii). Baker Academic.