What is anxiety? What does it feel like!? What does it do to us?

To answer those questions join me on a walk with my cat, down the lane behind our house.

Katie loves walking with me; she sets off, tail up, trotting along eagerly. But there’s a problem: 3 doors down lives a large dog. So Katie and I walk cautiously past that house. She stops at the gate and goes very still and quiet, looking and listening – is the dog outside or inside? If the dog is outside she freezes, her tail gets bigger, her fur fluffs up, and as soon as the dog spots us and starts barking, Katie backs slowly away. I can see that the dog is on a leash and actually is no threat, but there’s no telling Katie that.

What would happen if the dog was not on a leash, and came rushing out, chasing the cat? Katie’s ears would go flat back, and every muscle in her body would be flooded with adrenaline and she would zoom away in a flat panic. This is the ‘flight’ response.

But what if she got cornered, stuck unable to run? What would happen to Katie then? Instantly her whole body would change as she turned to face the dog, teeth bared, claws out, spitting, hissing and hurling herself at him in a wild attack. This is the ‘fight’ response.

There is one more, very different response to threat. If Katie was attacked by the dog, and she could not fight and could not run, she would play dead. Flop. Suddenly all the life would seem to disappear and she would make herself as small and as dead-looking as possible. This is the ‘freeze’ response.

Psychologists have for many years studied these very different reactions to threat. These make up our defence system. They are refined over evolution to protect us, and our animal cousins. We call these our Stress Response.

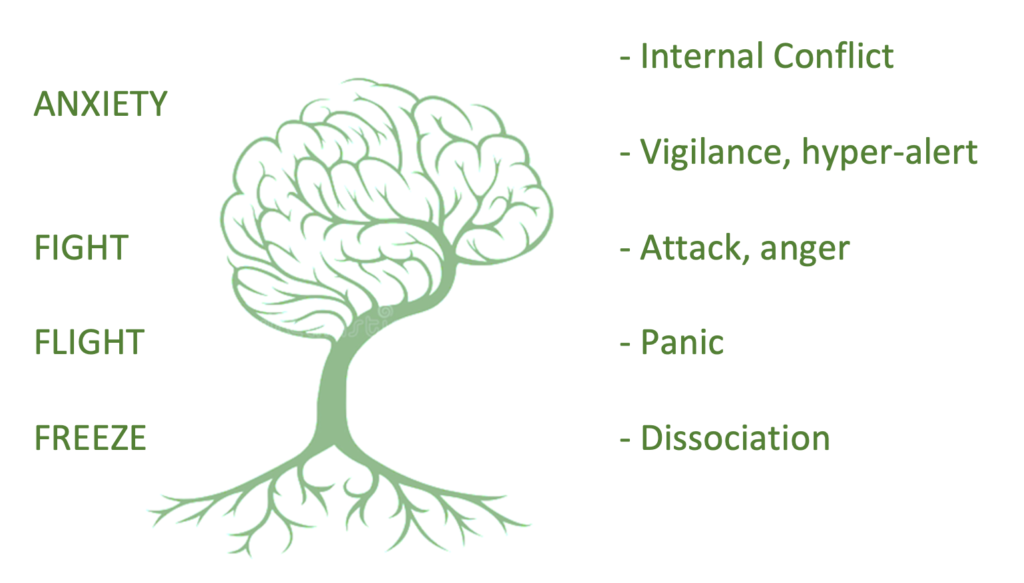

When we face a threat our brains trigger three powerful reactions, mostly before we’ve had time to think about it:

Flight, fight or freeze. Run, attack or flop.

If we map out these various responses to threats, we can map them in terms of which part of your brain is most involved in each different reaction. I am not a neuroscientist so I won’t try to explain brain structure or function. But I do know that your brain has the clever stuff at the front and the instinctive bits buried down deep sitting right on top of your spine, ready to burst into action without consulting all the clever bits.

Let’s start at the bottom.

The deepest, most visceral stress response is the ability your brain has to disconnect your mind completely. Shut down. The most extreme stress response. If you are totally overwhelmed with terror, you can’t think, you can’t act: you freeze. You can’t remember later what happened. We call this dissociation. Unplugged.

Next step up is panic. Every shred of energy goes into one thing: escape. Run. Flight. You know the sensation: fast heartbeat, queasy stomach, shakey, hard to breathe. In the Christchurch earthquake, some people described coming to and finding themselves in a totally different place, they didn’t remember getting there. They just ran.

Up from that is the response of anger. A fight response. Of course, some people prefer to be the dog rather than the cat – if in doubt, attack first! Not a great strategy for sustaining friendships, workplaces or marriages, but I get it. Most of us, however, only fight when we feel attacked, and then we can get pretty nasty and reach for any weapon at our disposal. At root, for most of us, fighting is a stress response to feeling under threat.

How do you experience fight, flight or freeze?

Can you recall the physical sensations of each?

What situations might trigger any of these reactions in you?

What strategies have you learned to cope with them?

However, my topic is not panic or anger but anxiety – which is related to each of these, but different in a very important way.

The flight-fight-freeze reactions happen in the face of actual threat. Or your brain can trick you into thinking that your life is in danger when really it’s not that bad. In NZ, thankfully, hardly any spiders can kill you, but plenty of people would have a panic attack if one lands on their head. However, that is not anxiety.

Anxiety is dealing with ongoing potential threat. Anxiety is my cat walking past the gate of the house where the dog lives. She wants to get to the other side, she enjoys walking with me, she knows she has to cross the danger zone, and so she steps forward anxiously. Her eyes get bigger. Her ears focus. Every fibre of her body is in the potential of attack. “Am I safe?”

So two key ideas for our map:

Vigilance: scanning for threats. Hyper alert. Checking and re-checking, alert, tense. This is very useful at moments such as trying to cross a busy road. But if you are in this state for more than a few minutes you end up in sensory overload. Too much information.

The second is Internal Conflict. This is where we are engaging more of our brain in the stress response. It gets complicated – because we want to step into something but we are also afraid that it will be bad. You want to get a degree, but you are afraid of failing. You want friends, but they might reject you. Different motivations compete with each other amidst a constantly shifting experience of risk.

Our brains were just not designed for 2022. We are trying to run a massive volume of information input into hardware that was designed for a far simpler age, with far more escapable problems.

I work in the area of climate change. The predictions are genuinely scary. Fear and anxiety for the future is totally rational. It is also counterproductive to stew in it. We see all of these reactions to the climate crisis: from the blanking out of total denial to the knawing panic to the information overload.

Our defence system is all good! It’s there to protect us from harm. God designed it. We share it with our animal cousins. The main difference for humans is that we struggle to extract ourselves from it. We are, perhaps, too clever for our own good. We can see so many potential threats in every direction. Are we ever safe?

My cat gets barked at, backs carefully away, then turns and runs helter-skelter back home, where she sits down, has a little wash, and then all the fear and anxiety has completely gone. If only it was that easy for us! It is not hard to get stressed, or distressed. The hard bit is de-stressing.

I have defined anxiety as being stuck in a state of potential threat. I have highlighted two aspects of anxiety: hypervigilance (constantly alert for risk, leading to information overload), and inner conflict (as we wrestle between what we want and the risks involved).

Which of these do you notice in yourself?

When you feel anxious, what does that do to your body? To your thinking? Can you describe the feeling?

When other people around you get anxious, what do you notice? How does this effect their actions?

When you are stressed, how do you react when someone tells you to “calm down”?

So what actually does work? What does help you to calm down?

A basic problem is that the stress response makes you less intelligent. It literally sucks the life out of your brain.

It also sucks blood away from your digestive system. It powers up your muscles and reduces the energy you have for important things like your immune system. Anxiety is bad for you. Or is it? What do you think?

What do you recognise as good stress in your life?

Do you need that deadline in order to push yourself to achieve?

Can you react to criticism with determination to learn?

Challenges are good. Threats are bad. How do we tell the difference?

Perhaps the question is – how do we grow in our capacity to respond constructively to challenges: from a parking ticket, to a deadline, to the massive problems of our world such as climate change?

What is the alternative to chronic anxiety in 2022?

Please read the 2nd blog in this series: 5 faith strategies for non-anxious living

This blog is part of a series on Anxiety by New Zealand Christians in Science. It was originally presented by Rev. Silvia Purdie as a talk for the chaplaincy team at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, NZ, for Mental Health Awareness Week in September 2022.

Silvia Purdie is a Presbyterian minister, counsellor & supervisor, author and climate activist. Read more by Silvia at Conversations: www.conversations.net.nz