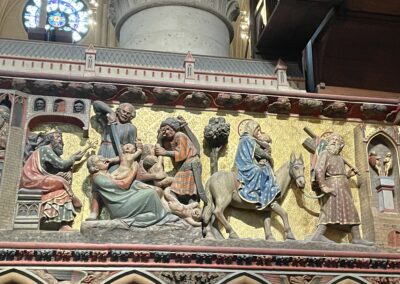

At Easter, in the liturgical traditions, we prayerfully enter into the drama of the cross

in the context of Israel’s history, and we let it do its work on us. This work is often

counterintuitive and independent of any particular theory of how the cross works.

At one level, we follow the betrayal and death of a man two thousand years ago, in a

brutal regime that terrorised much of the known world; the life of a man who lived

only 33 years. But this was a man who was known to have died and then risen

again—not quite in a body like ours, but not a ghost either. Only because of the

testimony to his rising do we notice him at all, name ourselves Christians, and call

upon the same spirit that raised him to also raise us and inform us of the life of God

and the inwardness of all things.

In the secular world, it makes no sense to rehearse the death of a man who lived in

an ancient city so long ago, before humans reached all corners of the earth, before

the Reformation, before the modern world, before industrialisation, and before

science as we know it. It makes no sense to discuss life beyond death. This

perspective may appear nonsensical to a secular world, yet it is not inconsistent with

science. Secularism and science are not the same thing. Secularism has many

definitions, but at its core, it is a way of thinking that obscures and ignores all that

falls under the heading of the spiritual or relegates the spiritual to a lesser category

than the physical and observable. Science, on the other hand, is concerned with all

that is real and prominently includes orders of being that are essentially invisible,

almost infinitely far away, or infinitely small, and which adhere to laws that, while only

partially understood, are unintuitive and remarkable. The boundaries of the

observable continue to expand. A life of science can prime us to respond to God and

the story of the death and rising of Christ.

But science acts on us and informs us in complex ways. Our understanding of the

Trinity is often subtly influenced by a mechanical reductionistic form of science or

scientism. There is a pervasive view of the world as a huge machine that has been

built up by a superficial view of science and of simple causation, that influences our

theories and views of everything including theology. Science, for instance, has

overwhelmingly provided us with a view of the world through the lens of causation,

specifically of a Euclidean/Newtonian nature. Even God is seen as a First Cause.

Many theories of atonement are grounded in causation. For instance, God the Father

caused the Son to die so that God’s honour could be reclaimed, or God the Father

achieved victory over the devil.

But what if we and God resembled the mysterious workings of quantum mechanics,

sometimes manifesting as one thing (a wave) and at times as something else ( a

particle)? What if our connection with Christ was more akin to entanglement, where

having once been linked ( in baptism and the Incarnation), we are now forever

intertwined—at a distance? What if, just as energy and matter are interchangeable at

subatomic levels, appearing and disappearing, God and we are also engaged in a

subtle interchange of energy? What if this energy is the costly love at the heart of the

universe. This is the universe that is also strangely turned away from God, and in the

shadow of that turning, we too suffer and, along with the world, contribute to that

suffering. There is a coming and going, a turning and affirming, a presence and

absence, that signifies a drawing into the life of God through Christ and by the power

of the Spirit. Easter speaks to the infinite cost of our collective moral error. Perhaps

that resonates in this day and age. Only something “costing not less than everything”

can make all things right. (Out of the Silence, Jim Cotter, 2006)

We must, though, return again to the man Christ, for Easter is about the scandal of a

particular man who died and rose again. Science alone, neither in its subtle forms

and in its reductionist ones, can get us to Christ. We need also to experience the

impact of Christ through the Spirit—who is nevertheless also the one in whom all

things hang together. There are mysterious aspects to the Incarnation, but they

include the idea of union with Christ–he is the vine; we are the branches, together

with an exchange of spiritual energy so that Christ’s fate and ours are somehow

linked, both the agony, the suffering and the resurrection and new life. In Christ there

is a sober view of suffering as a continuation of the life of Christ, but a life that is

always anticipating a life that comes out of death. To be a Christian is to be open to

the world and to possibility and to yearn for that which is not yet, but is discerned in

the fabric of the universe, in signals and signs from the present life; signals and signs

that speak of eternity.

To be made of matter is to die, but our hearts carry the burden of eternity. For this

reason, our failures are so costly because there is rarely the time and energy to

repair what is broken. Our spirits touch the Spirit of God, and we are sometimes

aware of the presence of angels. We sense levels of existence in and around us. We

love within matter as our only known home, but we also acknowledge that we have

another home, and that Jesus, who has returned to the Father, will take us there with

him in the fullness of time. However, our work now in this world—and our deep

investigation of it— is given inestimable value by the life of Christ. Whatever

salvation means, it is not just waving a magic wand; it necessitates a costly

incarnation and bearing all the joys, fears, grief, love and temptations of being alive

in the stuff of matter. It involves bearing the weight of the fear and longing of the

world. This is the world we discover and partially create through scientific endeavour.

And science, at its depths, models the subtlety and complexity and, ultimately, the

inexhaustibility of the spiritual. As Werner Heisenberg said, “The first gulp from the

glass of natural sciences will turn you into an atheist, but at the bottom of the glass,

God is waiting for you.”

May we all experience the joys of Easter and the experience of the waiting God.